Life

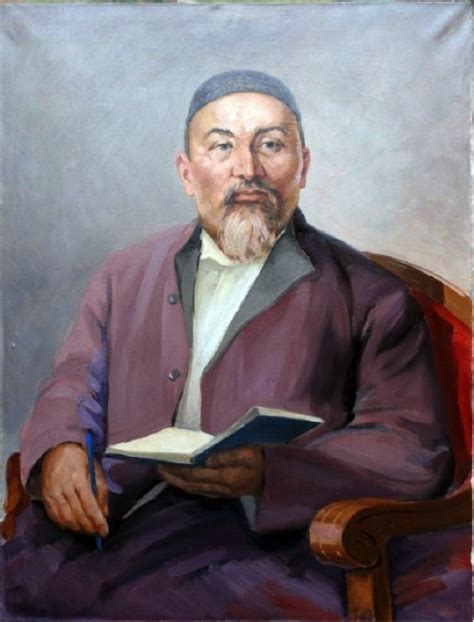

Abai Kunanbaev, the great thinker, enlightener, poet, and composer of the Kazakh people, was born on August 10, 1845 in the Genghis mountains of the Semipalatinsk region1. His father, Kunanbai Uskenbaev, was a highly influential elder of the Tobykty Clan, part of the Middle Juz. Abai was educated at home by a mullah, later in the Semipalatinsk madrasah (medrese), and in a Russian school. He studied the Holy Koran, foreign languages, including Arab and Farsi, and read the works of Eastern poets and scientists such as Firdousi, Navoi, and Avicenna. Although a deeply religious man, Abai has also been praised as Kazakhstan’s supreme enlightener.

Abai’s father had high hopes for his son, expecting that one day, he would be his loyal aide in all legal matters relating to other clans, which were often fraught with conflict. To some extent, Abai justified these hopes – he became one of the most famous law experts of his time. However, he was also influenced by classical humanistic ideas and suffered from the unforgiving cruelty of his environment caused by Russian colonial rule and native patriarchal tradition. Among Abai’s Russian acquaintances were several exiled intellectuals whose liberal ideas influenced him. Abai viewed it as his mission to acquaint Kazakhs with the accomplishments of world literature. He rendered some of the best translations of the works of Pushkin, Lermontov, and Krylov, as well as Byron, Goethe, and Heine into the Kazakh language. Another major influence on Abai’s thinking were classical philosophers – Socrates, Plato, Aristotle.

By the age of 35, Abai began to devote serious attention to his own poetry. His poems quickly gained fame throughout the steppes, being spread by word of mouth2. But due to Abai’s natural modesty and the questionable status of poets in society, he attributed his works to others, denying that he was the author. Only in the summer of 1886, he signed a poem (“Summer”) with his own name. Eventually, these poems made Abai hugely popular throughout the Kazakh steppes. He introduced a number of new prosodic forms into Kazakh literature, for example, the hexameter. Abai was the first to create a cycle of poems dedicated to the four seasons: “Zhaz” (“Summer”), “Kuz” (“Fall”), “Kys” (“Winter”), and “Zhazgytury” (“Spring”). He also created satirical verses mocking opportunism and kowtowing toward powerful administrators. His long narrative poems such as “Iskander” (dedicated to Alexander the Great), “Mazgud,” and The Legend of Azim,” solidified his reputation as the leading poet of the Kazakh people.

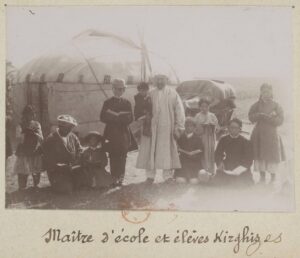

Abai’s aul attracted numerous akyns, but also foreigners – including Tatars and Russians – who wanted to witness Abai’s wisdom and artistry first-hand. While handwritten copies of Abai’s works were circulated among readers, it was the akyns who learned them by heart and performed them throughout the country. Abai also was a gifted composer who created tunes for his poems, which made them even more popular. As the great scholar and writer Mukhtar Auezov put it: “He carried his poetry like a burning torch through the gloom of ignorance and prejudice that enveloped the Kazakh steppes, revealing new horizons to his people and the promise of a new dawn.”

A major formative factor in Abai’s upbringing was his contentious relationship with his authoritarian father, whose plan it was to raise Abai as his successor. Kunanbai had four wives who competed against each other. But Abai’s mother, Ulzhan, and his paternal grandmother, Zere, showed Abai the possibility of a life based on values other than power: justice, truth, respect for all human beings, compassion, and mutual help. It was his mother who called him Abai, meaning “the thoughtful one”, rather than Ibrahim, his official first name. And since “thoughtful” was such a fitting description of the boy’s personality, it stuck to him forever.

Abai was a widely respected intellectual whose opinion was valued, including by the Russian administration, especially in legal conflicts. But in his life, he had to face numerous tragedies. He lost two of his sons to tuberculosis in 1895 and in 1904. Struck by grief, his own will to live waned quickly. Abai died on July 6, 1904 and was buried in Zhidebai. In the 1940s and 1950s, Kazakh writer Mukhtar Auezov turned Abai’s life into a four-volume epic, arguably the greatest achievement of Kazakh literature: The Path of Abai (Abai Zholy). Auezov created a veritable encyclopedia of Kazakh culture and customs, unparalleled in its richness and psychological depth. The Kazakh people’s multi-layered nomadic society with its complex relationships, encompassing both time-honored traditions and irrational excesses, is shown through the prism of Abai, a decent man, loyal friend, passionate lover, and deep thinker. This novel is more than a fictionalized biography: it is the portrait of a nation.

As with all great artists, Abai’s legacy has been interpreted differently in each subsequent period. Soviet specialists put the strongest emphasis on the social relevance of his work: whereas in the 1920s, the focus was more on the individualistic and spiritual aspects of his texts, in particular, the suffering of the intellectual in a world that largely disrespects education, in post-Soviet decades, the national specifics of Abai’s oeuvre became prevalent. Reading Abai’s poetic texts today, it is clear that they contain multiple elements and allow for a variety of interpretive approaches, all of which are legitimate in their own way. However, the surest method to understand Abai in a way that is true to his original intentions3. It is not an exaggeration to say that any exploration of Kazakhstan without an immersion in the legacy of Abai would be incomplete.

Poetry

Nature

Abai used poetry to capture the atmosphere of the aul and the steppe during different times of the year. His cycle on the seasons is particularly remarkable as it deviates from typical perceptions of nature in other national literatures, giving Abai’s poetry an unmistakably Kazakh dimension. “Autumn” (1888), for example, emphasizes darkness and not the celebration of plentiful harvesting, whereas “Winter” reflects existential danger, conveying a unique attitude toward forces of nature that defines the life of Kazakhs for many months. In Abai’s poetic world, winter appears as a person, and it is not a friendly one:

His beetling eyebrows are knit in a frown.

When he tosses his head — dismal snow starts to fall.

Like a crazy old camel he acts in his rage,

Rocking and shaking our yurt’s thin wall.The horses in vain try to shatter the ice —

The hungry herd scarcely shuffle their feet,

Greedy wolves — winter’s henchmen — have their fangs;

Watch, or disaster your flocks may meet!4

Unlike winter poems in other national literatures, Abai’s points to this season’s deadly consequences for people and animals alike: neither is it associated with the glittering beauty of fresh snow, nor the purity of the blue winter sky, nor the vastness of white fields or the joys of sleighing, skiing, and skating. Instead, Abai shows all the dangers that winter brings. Metaphors, such as wolves acting as “winter’s greedy henchmen,” point to an impending doom, a darkly existential dimension of this season in the Kazakh people’s perception. It seems safe to say that in his nature poetry, Abai is the authentic voice of his nation: he expresses the emotions that he, just like every Kazakh, experiences in his interactions with the forces of life. For the inner tension of these poems it is essential that the auctorial voice is not that of an outside observer. Rather, he and his people are one, his viewpoint is theirs.

Love

Nature often serves as the backdrop for love and passion:

In the silent, luminous night

On the water the moonbeams quiver.

In the gully beyond the aul

Tumultuous, roars the river.The mountains respond in a choir

To the shepherd dogs hidden from view.

You come in a flowery dress

To your midnight rendezvous.At once both bold and meek

Full of sweet girlish grace,

You furtively look around,

Blushes light up your face.Not venturing even to speak

With a soft half-sigh, half-groan

On tip-toe you rise and press

Your trembling lips to my own.5

In this poem, written in 1888, nature provides shelter, a hideout for the lovers. Human emotions live in harmony with the movements of the trees, the moon, and the river. In this and other love poems, passion is captured as an overwhelming, tormenting, but ultimately gratifying power. The erotic candor of Abai’s love poems is remarkable in itself, demonstrating how the poet fully embraces all aspects of love, including the physical.

Didacticism

In his didactic poems, Abai takes on the role of a teacher of life who explains to his listener, or reader, the rules of which principles they are to follow and which to avoid. The generalizations of these poems appear quite authoritative. However, the arguments expressed to the listener/reader are not normative in the conventional sense, verbalizing officially sanctioned rules for life. Rather, they are derived from what Abai himself learned in life, such as in the following poem written in 1889:

When your mind is as keen and as cold as ice,

When hot passions burn in your petulant heart,

Both fiery passion and patient thought

Must be ruled by the will, lest they stray apart. (…)What use is the mind without passion and will?

For a thoughtless heart even midday is dark.

Be able to keep all three in accord.

Let your will make your heart to your reason hark.6

The poetic form gives these conclusions a crisp shape but also makes it more persuasive in its didactic purpose.

The Mission of Poetry

In his poetry, Abai often asks himself: why do I use the poetic form in the first place? Who is my target audience? And he answers with a stringently formulated credo:

Not for amusement do I write my verse,

Nor do I stuff it full of silly words.

It’s for the young I write, for those

Whose hearing is acute, whose senses are alert.

Men who have vision and are quick to give response

Will understand the message in my verse.7

Abai’s poem confirms his identity as a teacher of life, an identity he has acquired through many hard lessons. Being privy to hearing or reading his poetry is the right of those who are open to those lessons, to shared experiences; those who are eager for entertainment should look elsewhere.

Philosophy

Philosophical questions are at the center of several of Abai’s poems, addressing existential aspects of our life here on Earth and thereafter. One of these poems, written in 1895, begins with a seeming paradox: Nature may be mortal, but humans are not. For a Western reader educated in a rationalistic framework, this is a paradoxical statement, as the opposite seems to be true: human beings exist in the world for a limited time, while nature in its universality will always be there. But Abai’s worldview is rigorously anthropocentric8. The supremacy of humanity in the universe, the fundamental respect for human potential and accomplishments turns the relationship around: Nature is mortal, humans are immortal! Abai’s radical reversal of the conventional relationship between humanity and the universe is rarely found in Western poetry; it is hard to say whether this is a demonstration of the primacy of his religious views or whether Abai speaks strictly within a poetic paradigm. Conspicuously, his anthropocentrism has found a continuation in 20th-century Kazakh poetry, for example, in Suleimenov.

Maybe nature is mortal, but man is not.

Though there is no coming back

When he draws his last breath.

The separation of I and Mine

Only the ignorant regard as death. (…)This world and the other can’t both be loved.

The divine and the earthly must be divorced.

But a man’s no believer if he in his heart

Loves this world all too much, and the other perforce.9

The Nation

Among the central themes in Abai’s poetry is his nation. The Kazakhs are his people, but who are they, what are their values? Whenever Abai ponders these questions, he is a stern judge; his directness in addressing national vices, as he sees them, is both awesome and terrifying.

Oh my luckless Kazakh, my unfortunate kin,

An unkempt moustache hides your mouth and chin.

Blood on your right cheek, fat on your left —

When will the dawn of your reason begin?Your looks are not bad and your numbers are vast,

Yet why do you change your favors so fast?

You will never listen to sound advice,

Your tongue in its rashness is unsurpassed. (…)Kinsmen for trifle each other hate.

God bereft them of reason — such is their fate.

No honor, no harmony, only dissent;

No wonder cattle is scarcer of late.10

The sternness and directness with which Abai chastises his nation is astonishing; it is hard to think of other poets revered by their nations who would be able to express such critical sentiments. Indeed, there is no hopeful outlook softening his message – the only way the poet can talk to his people is in uncompromising moral certitude, with a candor that is almost merciless. The fact that the Kazakh nation nonetheless loves Abai reveals a willingness to put up with harsh words as long as they are perceived as truthful.

Autobiographical Motifs

When Abai speaks about himself, his will to verbalize the experiences of his life with utmost honesty outweighs any other consideration. This is particularly true of a number of Abai’s poems that sum up the results of his life struggles, drawing a balance of what he has realized over the years. Such is the poem “It pains me now.”

It pains me now to realize that I have tinkered

With nature’s gifts and lived my life in vain.

I thought myself one of the rarest thinkers,

But empty is my fame… Alas, I have no aim.Inconstancy and idleness are our greatest banes.

We put no faith in loyalty of friends.

Our warmth of feeling all too quickly wanes,

We cool too soon: a trifling hurt offends.I have no one to love now, and no friend.

In disillusionment I turned to writing verse.

When I was sure in heart, how without end,

How fascinating seemed the universe!My soul craves friendship, seeks it daily,

My heart is aching for it, and while I

Have never known a friend who’d not betray me,

I sing a hymn to friendship for all time!11

It is this uncompromising honesty about himself that earned Abai the right to judge his own people with unrelenting candor.

Abai harbored no illusions about humankind. He describes human behavior as dominated by greed, dishonesty, contempt for others, pride, and ignorance. But he insists that these same human beings, both as individuals and as a nation, are free to make moral choices. He knows human nature; he has observed it keenly and studied it deeply. He shares his insights, hard to accept though they may be, with those who are willing to accept harsh truths. These human beings can opt for the values that Abai holds dearly: education and knowledge, respect and decency, truth and honesty, peace and love. That is the message of Abai, Kazakhstan’s greatest thinker, an inconvenient sage. Because Abai’s poetry addresses such a wide array of themes, from nature and love to life, death, and the character flaws of the nation, it seems fair to say that Abai is a poet for all seasons. His universality, sensitivity, and truthfulness explain why Abai’s poetic legacy is alive and dear to Kazakh readers today.

- The region has been renamed Abai district, part of the Eastern Kazakhstani oblast. ↩

- Only much later did Mursent Bekin write down Abai’s poems. ↩

- This article deals exclusively with Abai’s poetry, not his major prose work, Words (Gaklii, 1890-1898), which will be the subject of another publication. ↩

- Translated by Dorian Rottenberg; cf. Abai Kunanbayev, Selected Poems. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1970, p. 58. ↩

- Translated by Dorian Rottenberg, op. cit., p. 60. ↩

- Translated by Dorian Rottenberg, op. cit., p. 76. ↩

- Translated by Olga Shartse, op. cit., p. 74. ↩

- In his opposition to a rationalist approach, he was followed by Olzhas Suleimenov’s poetic worldview: “Earth, bow down to Man [i.e., humankind]!” [Zemlia, poklonis’ cheloveku!”] (1961). ↩

- Translated by Dorian Rottenberg, op. cit., p. 133. ↩

- Translated by Dorian Rottenberg, op. cit., p. 32. ↩

- Translated by Olga Shartse, op. cit., p. 44. ↩