“To attain your goal and be faithful to your duty, you should foster constancy of purpose, determination and strong will, for this help preserve the sobriety of your reason and the purity of your conscience.

Everything should serve the cause of reason and honor.”

Abai Qunanbaiuly, Qara Sozder, Word 32.

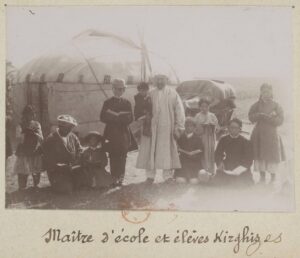

Kazakh writer and philosopher Abai is a canonical figure in Kazakhstani culture and society. The father of the Kazakh written literature, Abai, like Pushkin in Russia is considered an indisputable symbol of Kazakhness and even Kazakh statehood of contemporary Kazakhstan. In the past he was also canonized into the great revolutionary and the fighter for the Soviet values even if he died before the advent of the Soviet power in the Kazakh steppes. Many local Soviet writers considered Abai a “truly Soviet writer” and thinker owing to Mukhtar Auezov’s seminal text Abai Zholy about Abai’s life and revolutionary fervor for his people. The novel became the classical text of socialist realism but was also known as an encyclopedia of Kazakh culture. Many also believed that Mukhtar Auezov, a celebrated Kazakh Soviet writer himself, “saved” Abai from the historical erasure and cultural forgetting. Historical epopee about Abai’s life became an encyclopedic and historic genre of its own when the main character’s life and character development are described in great detail and contextualization along with the analysis of his surroundings and social change he creates.

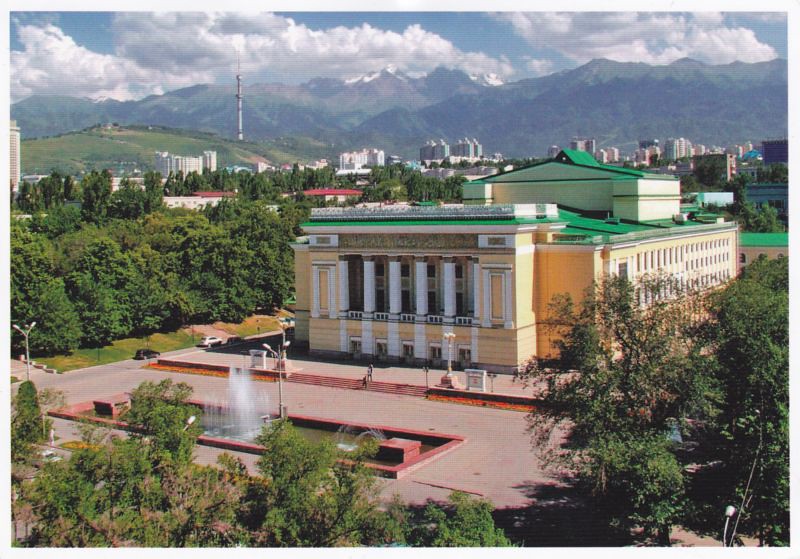

The canonical construction of heroes such as Abai and historical writing in novels remained in the heart of Kazakh modern literature of the twentieth century. During this time, in the context of Soviet propaganda and censorship writers used the historical novel genre to recount the stories and histories of their people by the way of writing and rewriting their nation in novels, plays, operas, and other literary genres. Abai became the canonized symbol and one of the first historical protagonists of the semi-biographical, semi-historical and realistic novel. Prior to the publication of the Abai Zholy novel, Auezov also wrote the Abai opera that is staged in Kazakhstan and in other countries’ opera houses till present. Through the canonical text of Abai Zholy that became the classical novel and “master plot” for socialist realist novel in Soviet Kazakhstan, as well as the country’s most celebrated novel in modern literature, Abai remained the undisputable and most popular cultural and historical canon. There were little attempts to re-think Soviet canon of Abai after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

After Kazakhstan gained independence in December 1991 Abai remained state’s main canonical figure in nation-building and cultural understanding of Kazakhs. “The nation’s salvation is in its spiritual [and cultural] rebirth. The path to this rebirth, as Abai fairly considered, would be long and difficult but it is necessary,” said President Nursultan A. Nazarbayev at the 1995 Abai’s 150th anniversary in Semey, Eastern Kazakhstan, the native land of Abai. The anniversary celebration in Semey in 1995 became one of the first spectacular events in post-independent Kazakhstan and attracted a lot of effort and attention from the local intelligentsia. The Abai monument in Moscow emerged in 1996 following these celebrations and as a part of the continued project of spectacular nationalism that engaged Abai as one of its symbols. There is even a street in the new capital of Kazakhstan – Astana – dedicated to the 150th anniversary of Abai. A major avenue of Almaty, the biggest city of Kazakhstan, also bears Abai’s name with the grand monument to the writer right at the beginning of the avenue that urban dwellers sometimes call put’ Abaia, Abai zholy or the Path of Abai imitating Mukhtar Auezov’s famous novel name and placing it within the city landscape.

But how Abai canon, that was formed historically, changes today within the intellectual elites, youth and other people? Some of the people call to reevaluate the “sacred” image of the Father of Kazakh literature and culture while others want to rethink his heritage, including myself.

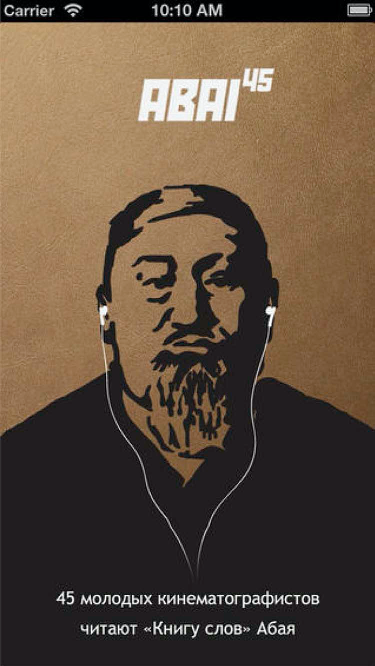

Many young intellectuals see the problem in the fact that Abai’s image is too literal, too Sovietized but his heritage is still not deconstructed and not analyzed fully again due to the Soviet legacy of reading Abai simply as a canonical Socialist Realist figure, a master plot. Everybody knows who Abai is but not everyone is particularly familiar or is capable of interpreting what Abai wrote about and thus he remains misunderstood. There is a growing necessity of re-thinking and re-reading Abai in contemporary context. Those Kazakh speakers who claim Abai’s sacredness and do not allow even the mere deconstruction of his heritage never question the problems of translation of his work from Kazakh (the original language) into Russian, for example. The Russian translation of Abai’s works remain a larger issue for those Russian speaking Kazakhs who continue to use the outdated and “not so perfect” Russian translation of Qara Sozder in the absence of a better translation. These discussions remain open and popular – groups of creative class youth create mobile phone applications to popularize Abai’s 45 philosophical essays Qara Sozder in Russian but the discussions about the adequate translation or even adequate initial transcription of this crucial text is still ongoing.

In his series of diaries and dialogues with long gone thinkers and writers, late legendary trilingual translator and writer Gerold Belger combined contemporaneity with heritage, he brought old writers, Abai among them, back to life to question the great thinker about life and problems of contemporary Kazakhstan. Belger used philosophical discussions (razmishleniya) in the urban settings when he walked up to the monuments of famous Kazakh writers and intellectuals, Dzhambul, Mukhtar Auezov, Abai. All of these intellectuals became canonized during the Soviet era when their monuments appeared in almost every city around Soviet Kazakhstan and the streets bared their names. Gerold Belger came to the monuments of these famous canonical figures to “speak” to them about the problems of contemporary Kazakhstan.

In one of these essays, Belger presents his imagined Abai’s discussion on the complex issue of “celebrated” and official writers in post-independent Kazakhstan, who like the Soviet intelligentsia, continued to serve the political elites in power instead of their own people. “Artistic talent is a Godsend,” says Abai, “[Artistic] oeuvre is a responsibility and an obligation, not a play.” Then Abai asks: Poet is a prophet, he is a connecting point between people and the real power so this is why any earthy power means nothing for the poet! If you are a poet, if you are called upon by your people, then why would you need any sort of tinsel, unnecessary things?! What can be achieved from such relationship, asks Abai – “I never received any awards and never suffered from that,” he concludes in Belger’s narration.

Belger’s attempt to seek more answers from Abai on contemporary issues shows that there is a need to continue studying the great Kazakh’s legacy. Kazakh youth are seeking the answers to their questions as well. A major local book store and publishing house also re-printed Abai’s Qara Sozder to raise more awareness among younger generation. The cover of the book featured the “modern” Abai – with a textbook old Abai picture but with a “glamorized” touch – perhaps to ensure better sales? Finally, in all of these discussions there was also a space for the Lost Abai discourse.

Following Gerold Belger’s quiet discussions with Abai-ata, his younger colleague and friend, Timur Nusimbekov followed the discussion about “abused,” misunderstood and “routinized” image of Abai in contemporary Kazakhstan asking that perhaps the real Abai is now lost? Nusimbekov just like Belger, reminded his readers that although Abai survived the great transformation of Time in the late nineteenth century and even if he was able to “step into the twentieth century” perhaps he still remains misunderstood by his own people. In Qara Sozder Abai talks about Kazakhs’ backwardness, laziness and their desire to steal, remain hateful and not spiritual in a bitter but also very revealing way – something that brought him a rather negative reception. “Abai who was abandoned by his own people,” writes Nusimbekov, Abai “remained in the depth of the inescapable pain and disappointment” yet Abai also remains “acutely contemporary Kazakh writer”. Two centuries after Abai’s Qara Sozder, lamented Nusimbekov “our society is the same in its love to inertia and backwardness” but the continuity that once connected Kazakhs to Abai is broken “technically Abai is our ancestor and technically we are his descendants (…) but we are too far from the real understanding of his [intellectual and philosophical] body of knowledge,” from the real meaning of Abai’s words.

Could it be that Abai was able to get to the heights that no one was able to reach yet. Maybe in those spaces he was able to see something eternal and unbreakable and he [Abai] was able to see the real eyes of the Eternity. Perhaps he concluded his lessons for us from there – about the beauty, about the Understanding of the limit and peace, lessons about love, wisdom and freedom. We are ignorant, lazy students [of his], sixteen million of souls and potential followers. But perhaps there is still a possibility that some of us would be able to take the lead and deal with Abai’s heritage in the most deserving way. And that would be the time when Abai would have his real birth day. And we will see something comprehensible, local, and lively there where right now we only see the monument to the misunderstood and strange Kazakh.

Ever since every child in my own “imagined community” of what some can define as post-Soviet Kazakhstan, was introduced to a sacred book of Abai’s “words” (Qara Sozder), it opened up an endless space of knowledge and self-reflection. Growing up as a bilingual (Russian and Kazakh) child in conditions of what now I know is called “multi-ethnic community” and definitely my “multi-ethnic” family, I had quotes from Abai’s Book of Words on my wall mixed with MTV posters. Well, that was the deal back in the days. I went to school that was named after Abai. In fact, in independent Kazakhstan every city, every village had to have a school named after Abai even during the Soviet period. We even still have a village and a region in Kazakhstan called after Abai. We grew up with Abai’s face on first Kazakh banknotes issued at the end of 1993 when Lenin roubles along with the Soviet financial infrastructure sank into oblivion. I remember my shock when I literally saw Abai at the Nauryz celebration for the first time as a kid. There he was in real flesh but with too much make up on – the legendary white-bearded wise old man, graciously entering the major public square for the theatrical celebration of spring equinox. I was even more shocked when I found out that a friend of a friend from a Kazakh school I used to study when in primary school was named Abai. The group of these same friends later in school years ferociously argued that every Kazakh child had to read Mukhtar Auezov’s seminal Abai Zholy, The Path of Abai novel only in Kazakh language and prior to doing many other things in life. So was my childhood in the era of “national awakening” in Kazakhstan. Abai to me was a grandeur monument set in stone, a legendary historical man who seemed to have his hand on every symbolic aspect of our national identity.

Thinking back to these days I wonder, if perhaps such a fixated idea of monumentalizing Abai when his voice was already so solid among so many different communities and readers, was so necessary. Qara Sozder remains the must-have book in every household in Kazakhstan along with other and more contemporary Kazakh literati. Abai’s oeuvre is translated into many different languages worldwide. When people in Kazakhstan call Abai “our Pushkin” meaning that Abai’s oeuvre and existence in our history and contemporaneity for 175 years is as influential in defining our culture and our place in the world as Alexander Pushkin is for Russian culture – unconditional and all-encompassing.

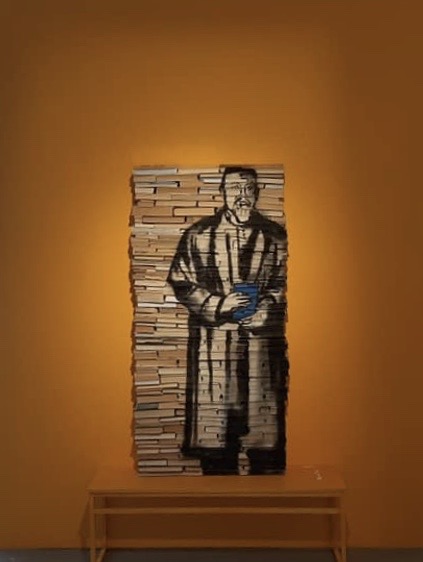

Even at 175, Abai never gets old. When Askhat Akhmediyarov presented his new installation combined from old Soviet books in TSE art gallery in the heart of Kazakh capital in January 2020, it only revealed the long-brewed thoughts. Even at 175, we, the people of Kazakhstan, are still searching back and rethinking the meaning of Abai’s words, re-reading Qara Sozder, and re-evaluating the wisdom of the lone steppe genius of the nineteenth century. As my childhood friends were saying, “Abai is in our minds, in our bones, in the soil of our land, and in our blood”. And similar to the mysterious notions of selfhood in any other cultures, Abai to me is a matter of almost a private space and a world of its own, the world that requires constant coming back to the source. In Abai I don’t see the limits of the “state”, ethnicity, tribe or even language. He and his wisdom are beyond the rigid structure of it all, just as much as some art and literature of present-day Kazakhstan, who, I hope continuously learn from Abai again and again.

This essay is adapted from Kudaibergenova, D. “Misunderstanding Abai and the legacy of the canon: “Neponyatnii” and “Neponyatii” Abai in contemporary Kazakhstan,” Journal of Eurasian Studies, Volume 9, Issue 1, January 2018, Pages 20-29