Courtesy of Personal Library of Former Ambassador of Kazakhstan to the United States of America H.E. Erzhan Kazykhanov

Eleanor Holgate Lattimore was born in Evanston, Illinois, where her father was on the faculty Northwestern University.

After graduating from Northwestern, Lattimore taught school in St. Louis and later organized girls’ clubs and camps for the Y.W.C.A in the North West. In 1921 she travelled in China with her parents. After two years in New York she returned to Beijing in 1924 where she taught for a year in Chinese schools and later became secretary of the Peking Institute of Fine Arts.

In 1926 she married Owen Lattimore, and has accompanied her husband on his many journeys in the exciting and little known lands beyond the Great Wall of China.

In her book entitled “Turkestan Reunion” published by Hurt and Blackett, Ltd. in 1934 in London, Eleanor Lattimore shares her memories of Kazakh hospitality and friendliness.

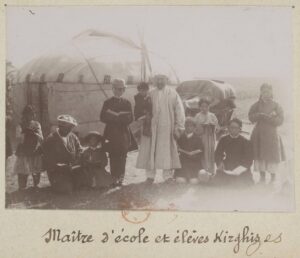

During their travels through Central Asia, Eleanor and her husband encountered Kazakhs who lived in the mountains. The author notes that “these Kazakhs of the Tien Shan live in the winter in the protected fastness of the high mountains, in the spring and summer moving farther and farther down towards the plains as the upper pastures are exhausted. All of their life is conditioned by the welfare of their flocks, but in June that life is prosperous and easy”1.

With fascination, Eleanor describes the Kazakh yurt that she visited during her travels. She notes that it was a beautiful yurt, a round domed room with colored felts on the floor, walls lined with a matting of wool-wrapped reeds, and with great arcs of woven woolen bands in geometric designs of dark reds and greens binding the square felts on to the framework which formed the doomed roof. In the middle of the yurt floor was a fire place, the author notes, beyond which they were invited to sit on a felt in the place of honor, opposite to the door. Behind them were piles of folded felts and colored blankets and all about the walls hung saddles and bridles trimmed with pewter or silver and enamel, leather bottles and bags and brass and pewter utensils of various sorts. This picturesque and detailed description of Kazakh yurt presents a valuable account of what it was like to lead a nomadic life centuries ago from perspective of a western female traveler.

Eleanor also says that during their visit to the yurt, they saw several large wooden bowls of milk on the ground near the door. She mentions also that Kazakhs largely live on milk, which they either eat as sour curds or boil in a large shallow iron cauldron to raise the cream, which they dry into hard cakes. According to the author, they use it too sweet or sour, in their tea, with which they sometimes eat small squares of bread.

She also shares very fond memories of their ride through a fragrant canyon of black spruces, which brought them out at more yurts on the far side of the first range of hills, where the hosts also were very warm and welcoming, preparing lamb dishes and offering guests kumiss – fermented milk of mares. Kumiss, Eleanor says, is very sour and a little furry in taste2.

Interestingly, Eleanor also shares her observations on the road to the Kazakh encampments in the soft freshness of early mornings. According to her it was that delicious time between spring and summer when the landscape looks like a Swiss advertisement for milk chocolate or summer hotel, bright green grass, bright yellow buttercups, bright blue sky. She reminisces how along the journey they were passed by Kazakhs galloping on ponies, tearing over the downs and almost straight up a steep hill side to join men waiting at the top to practice for a race.

As a woman, Eleanor could not ignore the beauty of Kazakh traditional clothes. She says that Kazakh women’s head dresses are lovely, a sort of white bonnet fitting tightly over the head and around the face and coming down over the shoulders in a flaring cone, with a strip of embroidery, usually red cross-stitch, under the chin or in a band across the forehead.

The young girls, Eleanor describes, are bare-headed, with their hair in long plaits, and they have bright beads and buttons sewed in rows on the front of the bodies.

The author writes that she wanted to buy some of their rings, heavy squares, ovals or octagons of silver with quaint designs traced on them.

Overall, Eleanor’s book provides an unique and detailed description of her journey through the region and her encounters with the Kazakh people. Our readers would certainly enjoy this beautiful volume that provides its very own and unique view on the Kazakhstan of the 1930s.