Abai embodied Kazakh tradition and cultural pride, but he was undoubtedly a modernist. We gathered the interviews of several Kazakh intelligentsia on Abai’s lasting legacy.

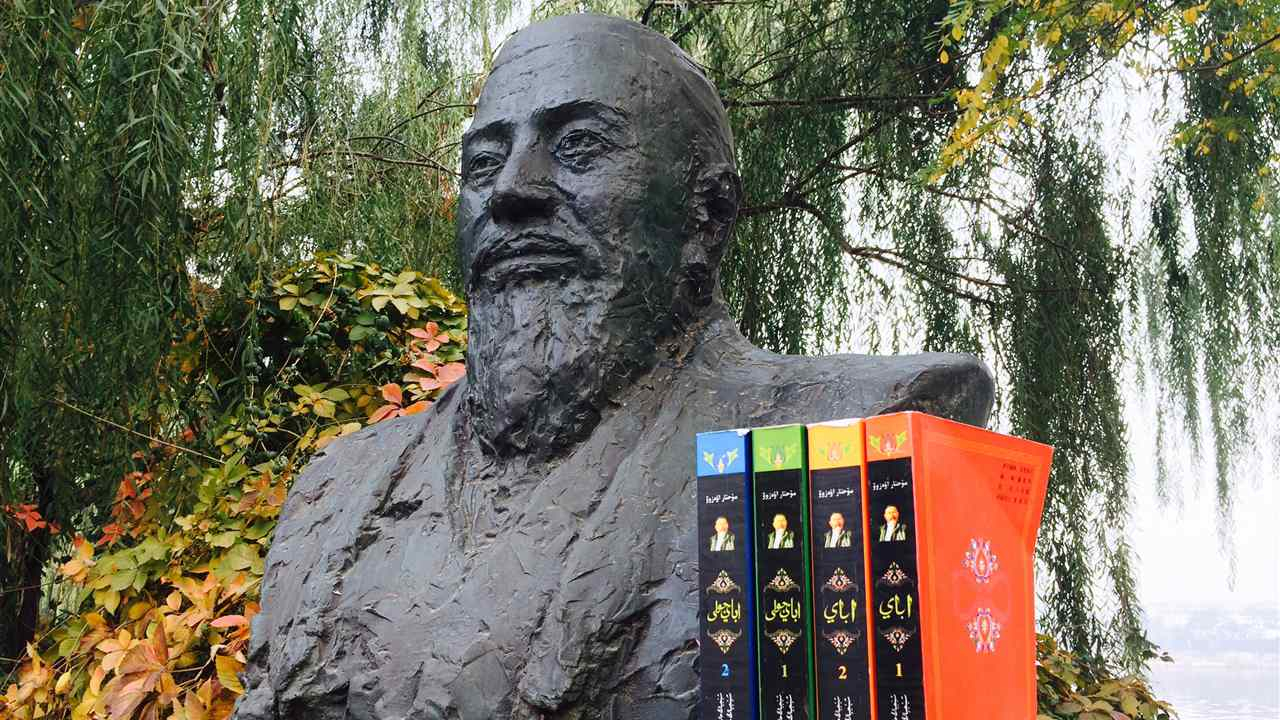

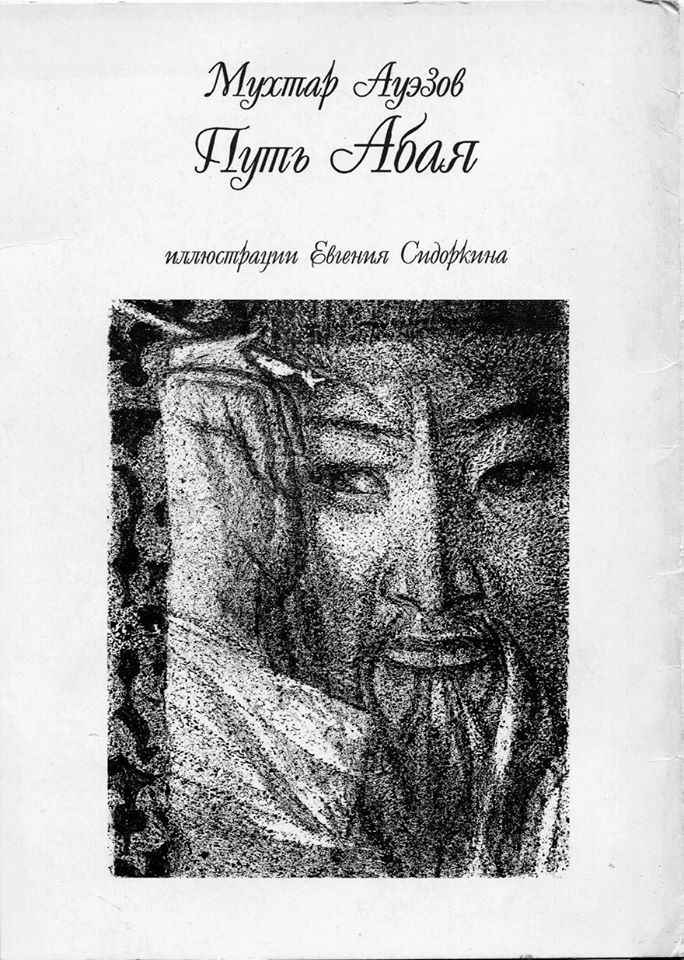

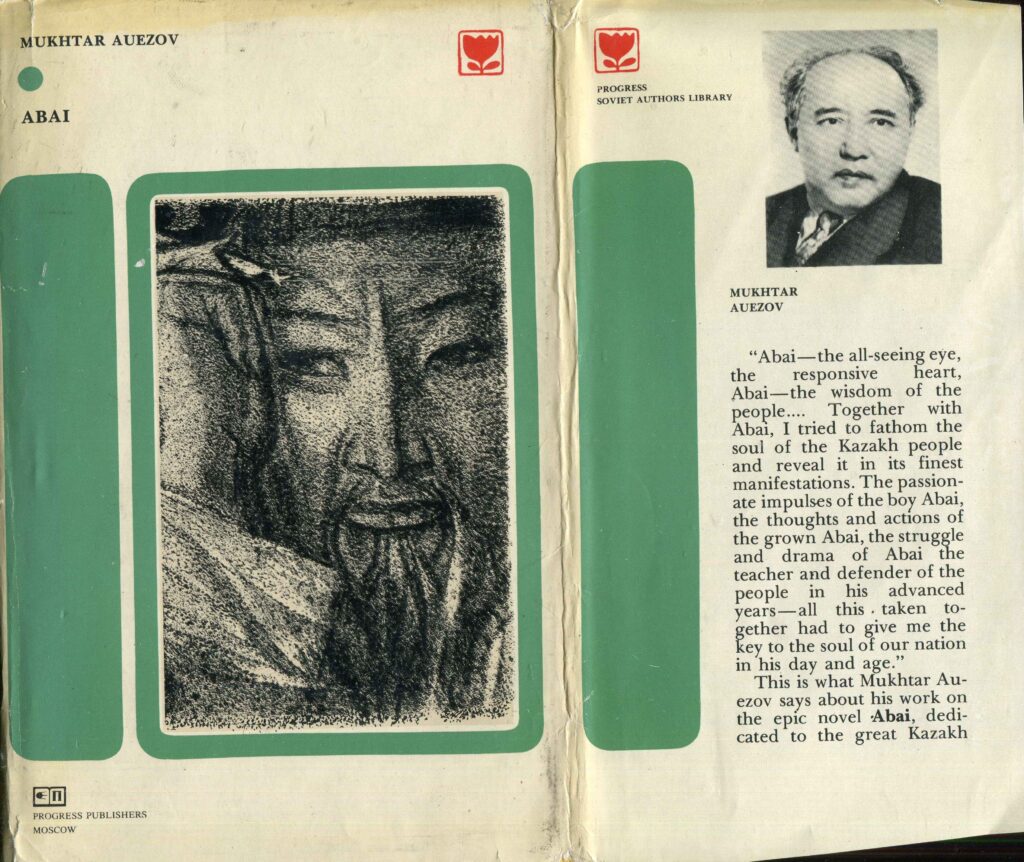

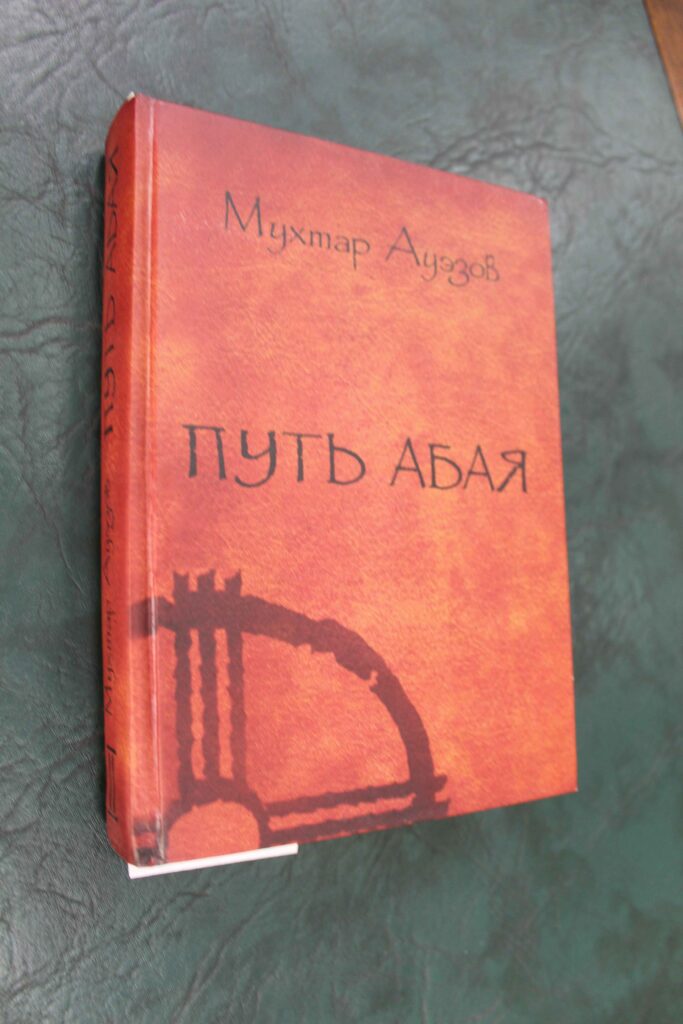

Abai was undoubtedly a modernist, paving the way for Kazakh literature—which was mostly oral at the time—to become sophisticated, emotional, philosophical, and political. His own “path,” famously depicted in Mukhtar Auezov’s epic novel The Path of Abai (Abai Zholy), is still curious. How did he develop his peculiar view and language? What are his philosophical grounds? How did his inner Kazakhness transform into something new and modern, providing inspiration for the entire Kazakh society and for generations to come?

We sought answers to these questions from some prominent representatives of the Kazakh intelligentsia.

Didar Amantay, writer, screenwriter, and philosopher, says that Abai played four major roles:

- He was the founder of the Kazakh written literary language.

- He laid the philosophical foundation for Kazakhstan’s national philosophy and language.

- He was a poet-modernist.

- He was an enlightener (he felt it was important to spread knowledge as much as possible).

The philosophical views of Abai are difficult to fit within a systemized thought structure as they had a deep connection with the national Kazakh way of thinking and imanigul, the doctrine of the perfect person (tolyk adam). For Abai, both God and man—and the entirety of humanity—are all one entity: “God created everything, and therefore He loves his creation, and the mission of each representative of our race is to love God and all of humanity forever.”

At the same time, Abai was concerned with how modernity would affect Kazakh nomads and whether or not nomads would be able find new ways to get by in the future, in the era of upcoming capitalism. Abai was able to grasp the essence of the time and formulate its main theses in his work, showing the way for a relatively young nation. Abai is a modernist in verbal art, a reformer in his criticisms and judgments, and a teacher in his instructions and covenants.

Rabiga Kulzhan, philologist and translator, maintains that Abai knew Kazakhness very well, with all of the pros and cons of the mentality:

It was Abai who launched the process of Kazakhs’ integration into global culture. The central idea in Abai’s prose is: “Orys bolgyn kelse, aldamenen qазаq bol! / Russians see the world, be with them!”—where Russians are seen as the representatives of Europe or global advanced culture more broadly. What followed was the very rapid integration of Kazakhs into the modern world.

During Soviet modernity, Kazakhs learned fast, and Kazakh-Russian mass bilingualism has become a tool of massive enlightenment. Abai has a separate monologue in “Kara sozder.” Mukhtar Auezov himself thought to name his epic novel with a purely Kazakh metaphor: “Telkara,” which means “A child of two queens.” (This refers to two cultures: east and west). But since there was no such equivalent in Russian, he picked a more understandable title: “Abai Zholy / The Path of Abai.” Auezov himself had a path similar to Abai: he began to write, like Abai, in Arabic (in a new method of Jadids), then he switched to Latin and later—after studying in Russia—to the Cyrillic alphabet!

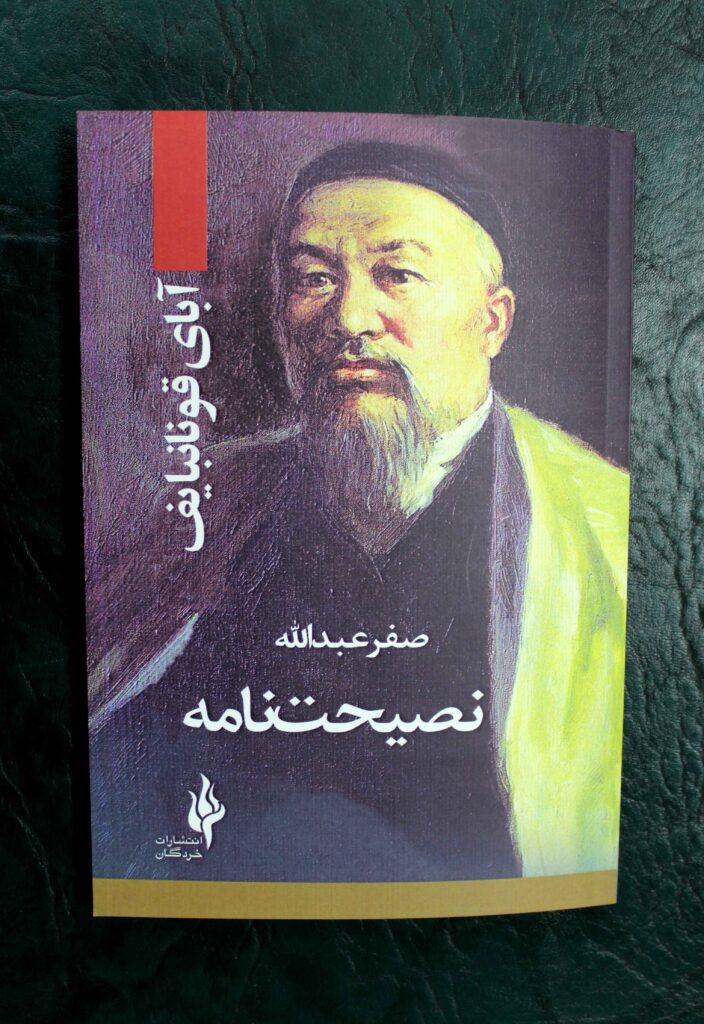

Abai’s modernism had a far-reaching, enlightening mission. Some of his thoughts are still worth investigating today. For example, his 38th poem (word) still needs to be translated with a deeper understanding of the religious and Sufi messages of the original.

Tilek Yrysbek, poet, translator, and designer:

As the writer and intellectual Askar Suylemenov once said: When the Kazakhs become wiser, Abai will become obsolete. In my opinion, Abai will never be outdated, but will become a tradition. In the words of Abai: “Yesterday’s cliff is the same cliff today.” This truth can also be attributed to Abai himself. Nothing has changed in our society since the days of Abai, and he would have criticized our generation bitterly as we are very far from his ideal of the “perfect men.” The loneliness of a sage is endless. But to understand the Kazakhs, knowing Abai alone is not enough.

After all, there were many figures that preceded him, such as Korkyt, Kurmangazy, Makhambet, etc. We also have to study Tengrianism and nomadic civilization. Abai sought to change the Kazakhs by preserving our cultural heritage. His 45 words of edification are full of humanistic ideas. Therefore, he is our steppe sage. And his words refer not only to the Kazakhs, but to the whole world.

Murat Auezov, a scholar in culture studies, is convinced that Abai was the savior of the Kazakh people:

He lived in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This time was a farewell song of the horse-nomad civilization. The nineteenth century of the nomadic steppe was the last century of freedom, and already it felt the forthcoming catastrophic changes that were yet to occur. The inner feelings in the steppe, expressed in its songs and poems, are very elegiac and sad. Great poets, singers, musicians, and heroic personalities appear in the steppe—those who understood the inevitability of tragic upheavals—and they foreshadowed the onset of apocalyptic times.

Kazakh language, folklore, and songs of those times loomed the threat of extinction, announcing that the space of the steppe is shrinking catastrophically. Dospambet, the warrior and poet of the 16th century, speaks of the same thing. He admires the beauty of his native land, but writes as if he were seeing this elusive world of his homeland for the last time. Abai shared the anxiety of his predecessors who were also looking for ways to the future. His genius was that he found these paths. He was well equipped with knowledge, beliefs, and a sense of future. Abai studied Sufism and ancient and eastern thinkers, even as far back as the brilliant Karakhanid era (942-1210).

One of the most prominent representatives of this era was Ahmed Yasawi, who was trying to combine canonical Islam with the nomadic traditional worldview of nomads, Tengrianism. Yasavi showed that one can find a way out of dramatic situations with the help of knowledge. He elevated the category of the “Teacher-Student.” Just like his great predecessor, Abai sought to acquire new knowledge. Fate provided him with excellent opportunities for this, such as the cities of Irtysh with their libraries and highly educated people from among the exiled Russian intelligentsia. Abai, whose word is gaining more weight, appeals to Kazakhs to send their children to schools. And the steppe responds to his call.

Patrons were found, and schools were opened in Turgay, Bayanaul, and Semirechye. The best students from these schools continued their studies in Moscow and St. Petersburg. They received a brilliant education. It was they who subsequently created the Alash party. Alash Orda and its most prominent members are, of course, the chicks of Abai’s nest. Khan Kenesary did not succeed in putting together the Kazakhs, but Abai succeeded. He opened for the Kazakhs—with their “Tіl, Dіl, Dіn (Worldview, Language, Religion)”—the path to the 20th century.

Abai Zholy

Abai Zholy is one of the most popular and valuable novels written by Mukhtar Auezov. The first book of the series was published in 1942 and after five years in 1947 Abai, the second of the series was published, then came the third book in 1952 called Abai Aga (Brother Abai). Finally, the fourth book was released in 1956. Later all of the books were repackaged and renamed as Abai Zholy (The Path of Abai). The first book and second books each have 7 chapters and one epilogue. The third book has 6 chapters as has the Fourth and one epilogue entire epic is divided into 20 short chapters each of which includes uniquely interesting situations. “Writing about Abai was risky.” In fact, Auezov had to revive him from the ashes and defend him against ruthless censorship. In particular, in the novel The Path of Abai, censors removed seventy pages that describe how Kunanbay’s wife, Ulzhan, escorted him to Mecca. Auezov was often accused of archaism and nationalism by the Soviet authorities and had to defend himself.