In this interview, Peter Rollberg, one of the rare foreign specialists on Soviet Kazakh cinema, speaks about the first Kazakh filmmakers, their main themes and relations with the audience, and the legacy they left for modern Kazakh society.

Your book is titled The Cinema of Soviet Kazakhstan 1925–1991: An Uneasy Legacy—could you explain why you call it an “uneasy legacy”? Is it in some way a burden for independent Kazakhstan or just an uncomfortable memory?

The word uneasy refers to the complexity of this wonderful yet contradictory legacy. The title also points to current efforts in independent Kazakhstan to decommunize society. Such strategies always carry the risk of throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Fortunately, most Kazakhstani intellectuals have been skeptical of radical approaches, including toward national film history.

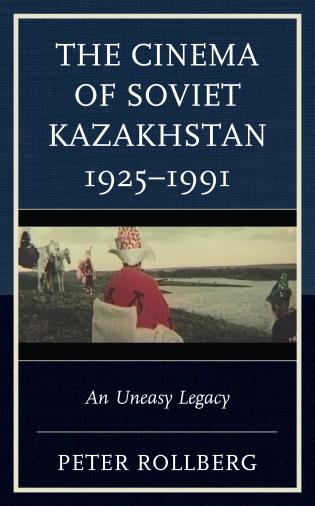

Peter Rollberg is Professor of Slavic Languages, Film Studies, and International Affairs and Associate Dean for Faculty Affairs and Research Initiatives at Elliott School of International Affairs of the George Washington University. Rollberg studied at Lomonosov University in Moscow and at the University of Leipzig where he earned his Ph.D. in 1988. His main field of expertise is Russian literature and film, as well as Georgian and Kazakh cinema. In 1996, Rollberg published volume 10 of The Modern Encyclopedia of East Slavic, Baltic, and Eurasian Literatures (Academic International Press) and in 1997, a festschrift in honor of Charles Moser, entitled And Meaning for a Life Entire. His Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema was published in 2009 (second, enlarged edition 2016). His book The Cinema of Soviet Kazakhstan 1925-1991: An Uneasy Legacy was published in February 2021 by Lexington Books.

Indeed, the modernization of Kazakhstan in the twentieth century occurred in a communist framework, and while its effects were sometimes horrendous, there were also undeniable accomplishments. Kazakh cinema, for example, boasts incredible achievements. Watching Mazhit Begalin’s His Time Will Come (1957) today, one can only marvel at its artistic robustness and national perceptiveness, and Begalin’s film is not alone in this. True, communist ideology permeated every sphere in Kazakhstan for seventy years, but the nation’s cultural output was shaped in such a complex manner that official ideological guidelines were just one factor among many. The more thoroughly we look at Kazakhstan’s film history (and music, and literature) today, the more will we be able to appreciate its amazing performers (from Hadisha Bukeeva, Eleubai Umurzakov, and Serke Kozhamkulov to Amina Umurzakova, Nurmukhan Zhanturin, and Asanali Ashimov, to name but a few), cinematographers, composers, and directors. Soviet Kazakh cinema is part of the country’s complex—and thus “uneasy”—legacy, but a legacy of which Kazakhs can be proud.

Sovereign Kazakhstan is reassessing its Soviet past and certain painful memories, such as the famine and purges of the 1930s, cast a dark shadow over everything Soviet. Yet Kazakh Soviet cinema seems to be enthusiastic and optimistic. Did Kazakh Soviet cinema or individual artists address the dark pages of the Soviet past? What are your thoughts on the process of rethinking everything Soviet?

Kazakhstani filmmakers, like the vast majority of Soviet citizens, were very loyal to the communist state. At the same time, however, they maintained a great deal of pride in their own culture, in their native heritage. Of course, there was always the threat that the center in Moscow would accuse them of nationalism, which could have dire consequences. But great filmmakers such as Shaken Aimanov were also skilled administrators and politicians who knew how to maintain the sensitive balance between deep love and respect for Kazakh traditional values and dedication to the idea of communist modernization. Of course, films that captured Kazakhstani reality in a harshly realistic manner (for example, Zhardem Baitenov’s excellent Blue Route, 1968) were reprimanded. But the long-underappreciated Abdulla Karsakbaev managed to expose the totalitarian essence of the emerging communist society in A Worrisome Morning (1966), and Damir Manabaev made one of the first honest films about the horrors of collectivization and famine, Surzhekei, the Angel of Death (1991).

Was there one Soviet cinematic tradition or form? How similar or different are Soviet films produced in different republics?

Kazakhstan managed to build its own cinematic world quite distinct from that of Russia, Georgia, or Uzbekistan. Important style-shaping components were typical native landscapes, alternating majestic mountains with dusty steppes and blossoming valleys—easily recognizable elements that we find in historical dramas, children’s films, and contemporary comedies.

Another component is the constant civilizational tension between countryside and city, with Kazakh customs and language dominating the former and Russian language and denationalized urban lifestyles the latter. By the way, Kazakhstani cinematography is outstanding, a genuine phenomenon that has not been sufficiently researched. Great cameramen such as Mikhail Aranyshev, Iskander Tynyshpaev, and Askhat Ashrapov were responsible for creating the essential visual peculiarities of Kazakh cinema. Of equal importance are the scores of Kazakh films—for example, without the life-affirming energy of Nurgisa Tlendiev’s music it is hard to imagine Abdulla Karsakbaev’s wonderfully humorous and poetic children’s films.

What is the peak of full-fledged national cinema in Kazakhstan? Which movies best represent it?

For the Soviet period, it is the 1960s. Films such as Begalin’s The Traces Go Beyond the Horizon (1963), Aleksandr Karpov’s Tale of a Mother (1963), Karsakbaev’s My Name Is Kozha (1963), Shaken Aimanov’s Land of the Fathers (1966), and Sultan-Ahmed Khodzhikov’s Kyz-Zhibek (1970) reveal the philosophical depth and aesthetic richness that Kazakh cinema developed within a mere decade. Unfortunately, the 1970s turned out to be a time of rapid decline, even if that period has its share of superb films, including Viktor Pusurmanov’s prohibited Where the Mountains Are White (1972) and Sharip Beisembaev’s Protect Your Star (1975). The Kazakh New Wave in the late 1980s was very important for the self-reinvention of cinema after the bankruptcy of communist ideology and socialist realism, but its target audience were cineastes rather than the masses that Kazakhstani filmmakers had attracted in earlier years. Some leading New Wave directors—Serik Aprymov, Darezhan Omirbaev, and Ardak Amirkulov, among others—are still active today and, albeit rarely, make highly original films.

You know the Kazakh film directors and their biographies very well. How could an ordinary Kazakh become a film director? What institutions existed to train such cadres? How good were they?

Filmmakers from all republics were educated at the All-Soviet State Film School (VGIK) in Moscow. Because the competition was tough, Kazakhfilm studio established a one-year preparatory course in the 1970s to help native candidates pass the entrance exam in Moscow—with mixed results. Sergei Soloviev taught a masterclass in the mid-1980s from which the Kazakh New Wave sprang. But the most influential Kazakh filmmaker, Shaken Aimanov, was an actor and stage director who had no special professional education as a film director, yet his best films are alive today, and some deserve to be categorized as auteur films.

Read more: FOUNDING FATHER. Shaken Aimanov: The Man at the Core of Kazakh Cinema

Central Asian art-house cinema usually garners more praise than its mainstream counterpart. Is this just because of the exoticness of the issues and visuals of Central Asia or there are some deeper reasons?

The split between arthouse and mainstream in Soviet cinema happened in the early 1960s. Each serves different purposes and both are legitimate, but for a financially sensitive art such as cinema, arthouse is difficult to maintain without state sponsorship. The Kazakhstani state has been unusually supportive of arthouse cinema, both before and since independence, because it earns the nation international prestige. Kazakh arthouse directors have responded creatively to such great film artists as Bresson and Bergman, but also Scorsese, while preserving their national peculiarities. The latter aspect makes them attractive for international festival audiences. This is also true of the youngest generation of Kazakh filmmakers, including Emir Baigazin and Adilkhan Erzhanov. They may now be at a point where an emerging native arthouse audience actively responds to their sophisticated narratives.

You ended the book in 1991. Do you have plans to write about independent Kazakhstan’s cinema? If so, how would you characterize the trends of the newer era?

The post-Soviet period of Kazakhstani cinema is difficult to analyze in a historical framework because it is more diffuse and the causality of certain trends is harder to assess. The country’s national culture and the State have been growing increasingly distant from each other. Interestingly, during a brief period in the early 2000s there was enough money to fund films of high artistic quality such as Bolat Sharip’s Sholpan’s Sin (2006). However, what was then lacking was an efficient distribution strategy, and as a result, many of the best Kazakhstani films remained virtually unseen. It was Akan Sataev who helped reconnect quality cinema with large audiences—indeed, his Racketeer (2008) is a masterpiece of cinematic storytelling and at the same time a highly entertaining thriller with a clever take on Kazakhstan’s transition to neocapitalism. More recently, Kazakhfilm studio has focused on large historical canvases such as The Road to Mother and Tomiris, but it is unclear how long this trend can last. Many Kazakh filmmakers and producers seem to be obsessed with the prospect of winning an Oscar for Best Foreign Picture, but in my view, that is a complete waste of energy. The Academy Awards have lost much of their prestige, and foreign winners have largely been forgotten very quickly.

Kazakhstan’s creative industry is a promising field, with such world-famous names as Timur Bekmambetov and the singer Dimash, as well as comedians who make careers in Russia. Do you think the Soviet artistic past can in some way be incorporated? Would you like to see any Soviet Kazakh films be remade?

In my view, Bekmambetov has done very little for the rebirth of Kazakh cinema in the new millennium. As a matter of fact, any attempt by Kazakhstani producers to imitate Hollywood’s special-effect-focused transnational patterns, as well as the casting of foreign stars, has only led to embarrassing flops. Remakes of film classics usually turn out to be critical and box-office disasters, but I would like to see young Kazakh directors connect with their national literary heritage, for example, Auezov. For the Kazakhstani film industry as a whole, the most commercially promising genre is comedy, in which directors such as the brilliant Nurtas Adambai have become real virtuosi. Recently, many impulses have transitioned from cinema to the Internet, where ultrarealistic serials attract millions of viewers.

Watch Kazakh Soviet films on the KazakhFilm Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/user/kazakhfilmstudios