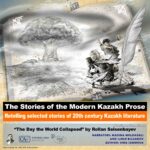

Rollan Seisenbayev, born October 11, 1946, in Semipalatinsk, is a prominent contemporary Kazakh writer, playwright, and translator. His novels and short stories have been published by some of the largest publishing houses and magazines worldwide. In addition to his literary activities, Seisenbayev is the founder of the Abai House in London, the Abai International Club, and the international literary magazine Amanat. He is the recipient of numerous international literary awards and is known for his masterful depiction of the effects of the Soviet nuclear tests at Semey on the Kazakh people. In the following story, he shares his first-hand experience of hearing nuclear tests as a boy in Semipalatinsk.

FULL TEXT

Now Rollan lives in the city. He often dreams of his father. He recalls the days when nuclear tests were going on in his homeland at the foot of the Chinggis Mountains. He still trembles from the underground explosions! Feels the pain and suffering. They were told that it was done for the good of the people.

In those days, in Semipalatinsk the earth trembled, houses’ windowpanes shattered. And once a young woman gave birth prematurely in one of the shepherd’s yurts at the foot of Chingistau. She gave birth in pain and suffering. It seemed that the fetus had felt the earth’s trembling. The child’s face is disfigured.

In the summer of 1953, trouble came to the people of Chingistau near Semipalatinsk. In a single hour it came… The children, grazing goats and sheep behind the aul, heard something terrible: screams, shouting, women crying. Leaving the sheep and goats in the steppe, they rushed to the village. And there something unimaginable was happening: people hugged, said goodbye, shouted, sobbed. Fuss, confusion, chaos—and the boys stood with their mouths open, completely unaware of what misfortune had so upset the inhabitants of our quiet, comfortable village. “Maybe a war has begun? With the Americans or with some other imperialists?” it dawned on one of us, and we began to eagerly look at the huge military vehicles and soldiers scurrying around everywhere, which seemed to have sprouted from the ground.

The boys boldly rushed to join the partisans; they did not yet understand the seriousness of the situation. The military appeared and said that there was no war, yet the evacuation began.

Adults fearfully prepared for the move, while the little ones rejoiced at the changes. Especially Rollan: he wanted to move to the city. Mom and grandmother were tying bales, there was real chaos in the house. The villagers began to say that the bomb had superhuman strength and could wipe Chingistau off the face of the earth. The physics teacher said that this bomb was worse than the one that the Americans had used to destroy two Japanese cities. That one was atomic, and this one was hydrogen.

Suddenly a loudspeaker hanging on a pole in the center of the village came to life and asked all the villagers to gather at the village central office. Rollan and his grandfather stood in the anxious crowd. The district officials came to the podium along with the military, and Rollan saw his father. He looked tired, his eyes red from insomnia, but he spoke confidently and calmly. In the evening, they were having dinner, and Rollan understood from his father’s short remarks that the residents would be evacuated to the city of Ayaguz; those who wished could even go as far as the regional center, Semipalatinsk. The old people were given permission to leave with their cattle for the Chinggis Mountains. So that was why big military vehicles had come to the village! In the morning, the lieutenant colonel said that people should take only the most necessary things with them, barring their windows with bales of straw. He promised the residents that in a month they would all return home safely. Each family was given five hundred rubles.

Rollan decided to stay with his grandfather and go to the mountains. He and his grandfather set off on the journey. Behind the aul, other old men and old women, who were supposed to go with the cattle to the mountains, also gathered. Rollan discovered that there were no other children. And then he noticed a little girl, Kenzhe, who was sitting on the cart with her grandmother. She smiled and Rollan waved to her.

Most likely the grandfather internally understood the real threat. How else can one explain his outburst? They looked at each other point-blank, the tall, stately lieutenant colonel and the round-shouldered but still powerful, sinewy grandfather, whose tenacious hand maintained a tight grip on the kamcha.

“Do you know, official man, what this people has endured? No, you don’t know. You do not know that our land is the land of great and holy people! For centuries we have lived in this steppe, roaming peacefully and offending no one. Here are our jailaus. Our Abai was born here. He then became uncomfortable to the authorities, and for the mere mention of his name we were exiled to Itzhekken—Siberia. Then they shot Shakarim, our great poet and philosopher, with whom your Leo Tolstoy was friends, and again—as soon as a Kazakh spoke of Shakarim, he would immediately find himself in Siberia. The best people were dying in exile… So you came from Semipalatinsk, so our entire steppe from the aul to Semipalatinsk was covered with human corpses—hunger, do you know what it is? Do you know how many died from famine? And then—the war. How many she carried away, then every second horseman on the other side fell. And look what the collective farmers eat, what do they get for their workday? Yes, we do not live, but we exist. Many have forgotten not only the taste of meat, but also the taste of bread. For each collective farm sheep, you can pay with your head … So tell me, official man, when will our people live? And will we live?.. You’re persecuting us to death… Isn’t that right?

The people listened in silence. People averted their eyes. They agreed with the old man, but they were frightened by his frankness, and some of them began to back away, schooling their faces into absent expressions—oh, we didn’t see anything, we don’t know, we didn’t hear …

“Where did they go? Stand and listen to the truth! Have you lost not only your mind, but also your honor?… Although in modern times, honor, you see, is an unbearable burden for many. But who will need you if you have neither honor nor conscience, huh? Have you thought about this?”

People froze in shame. And then Rollan’s father intervened. He said that an order was an order … However, at the same time, he also avoided looking directly into his father’s eyes. Rollan realized that he was now thinking about what his grandfather’s monologue would cost him. But he wanted his grandfather to tell the military man something else about our homeland. Rollan thought that it was unlikely that the mil itary man knew anything sensible about the Kazakhs. It was probably the first time he had seen Kazakhs. But then the lieutenant colonel went up to his grandfather and hugged him. “I understand you, father. We’ve all suffered. We have suffered like no other people in the world.”

Along the way, Rollan befriended Kenzhe.

Once they were told that everything would start soon, they ordered everyone to lie down. Kenzhe lay between Rollan and her grandmother. Her tender face was haggard, her wide eyes frozen with fear, her long eyelashes barely moving. His grandfather whispered a prayer… Her grandmother forcibly covered Rollan’s head.

Suddenly, their leader shouted loudly: “Attention! Attention! Everyone lie down! Freeze!”

And the earth shook softly. As if it was an eternal cradle, cradling us. But the earth suddenly shuddered, with frantic shocks it beat us from below: in the legs, in the chest, in the face. Grandmother’s arms loosened, the earth heaved like a wild horse; steppes, mountains in the last attempt held still, so as not to perish. I saw, looking out from under the felt mat, that a huge mushroom filled the sky, and fire-breathing flashes played with an unimaginably violent inflorescence of colors. Fear and surprise in a single moment fettered my soul, I had never experienced such a thing even in my worst dream. Mountains groaned, huge stones rolled down with a roar, trees creaked, bent, and another sound suddenly wove into these hellish sounds—a desperate, ear-cutting squeal, a cry? …I still don’t know how to properly describe this terrible sound. A little girl in a white dress was running, dodging bouncing stones. I myself did not notice how I got out from under the felt mat and, standing to my full height, stared numbly after her. The fiery mushroom rose heavily, bright flashes blinded the eyes, the little girl ran away along the shaking ground—to where, no one knew. I froze, as if rooted to the spot, not understanding what I needed to do. Her scream hurt my ears. Or maybe there was no scream? Maybe I imagined she was screaming? Maybe she silently opened her mouth and ran not into the steppe, but into the mountains, and the stones shied away from her. “She will die, she must be saved, we must run after her, catch up with her,” I thought, and shouted: “Kenzhe! … Kenzhe! … Kenzhe! …”

After the explosion, we lived in the Chinggis Mountains for another week and a half. Right there, on a high hill, they buried Kenzhe, the first innocent victim of the hydrogen bomb tests at the test site “near the city of Semipalatinsk.” The city of Semey—Semipalatinsk! A home town, dusty, inconspicuous, from that day on you became known all over the world! Semipalatinsk… Semey… Nevada… Test site… Atom… Tests… Why, Kurchatov, they say, immediately after this explosion exclaimed: “This is monstrous! It should never be tested against humans!” The military men disappeared just as suddenly as they had appeared.

Three weeks later, people were allowed to return to the village. Everyone rejoiced at seeing their children, grandchildren, relatives, and friends. Rollan was relieved to once again see his brother, his sister, his mother and, of course, his father, because he and the military had remained in the thick of it. Rollan and Kenzhe’s grandmother went to the girl’s grave. The grandmother said goodbye to her only granddaughter; Rollan said goodbye to his first childhood love. As time passed, he met so many people and has already lost so many, but he will never forget the little fragile girl Kenzhe. Her thoughtful look, a dazzling smile of white, even teeth, instantly transforming her.

The fifth of August. Father’s Day and August 5th. Twenty-five years ago (1963) in Moscow, representatives of the governments of the USSR, the USA, and Great Britain signed the Treaty on the Prohibition of Tests of Nuclear Weapons in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water. More than 100 states have joined this treaty. It was an unusual anniversary, perhaps the largest memorable date of this year, an event on a universal scale, a reminder of the day when a person felt like a man, not a murderer. This treaty was worthy of the people, and the people were worthy of the treaty.

***

The terrible events associated with the Semipalatinsk test site are reflected in Rollan Seisenbayev’s story “The Day the World Collapsed,” which is dedicated to the people of Nevada and Semipalatinsk. Through the eyes of a seven-year-old boy, the story conveys the tragedy of the people and their homes, juxtaposing their suffering and pain with the suffering of nature. The catastrophe facing the inhabitants occurs in parallel with the catastrophe of nature being destroyed. A calamity of such scale is unmatched in human history. Seisenbayev’s text is one of the rare instances of nuclear catastrophe—a real threat of the twentieth century—being described by a Kazakh author.