Courtesy of Personal Library of Former Ambassador of Kazakhstan to the United States of America H.E. Erzhan Kazykhanov

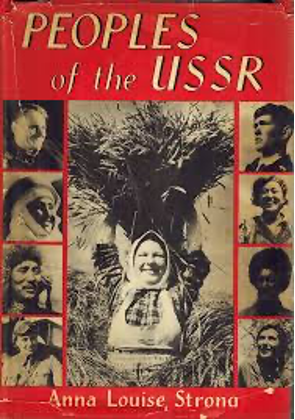

Anna Louise Strong (November 24, 1885 – March 29, 1970) was an American journalist and activist, who wrote over 30 books and varied articles. Although she left the United States just as the Communist Party was forming, her return visits from the Soviet Union and later from China and her many popular books kept her in the public eye throughout her long life.

In her book “Peoples of the USSR”, published by the MacMillan Company in New York in 1944, Strong devotes a chapter to share her experience of travelling to Kazakhstan.

During the second World War, Strong reminisces, an exhibition was held in Alma Ata – a city far in Asia at the foot of the Tien Shan Mountains, last stopping place in the USSR on the airplane route to China.1 The exhibits displayed the progress of science in Kazakhstan, of which Alma Ata is the capital.

According to Strong, Kazakhs are proud of their progress. They are proud of their great republic. It is the biggest republic in the USSR except for the Russian Republic. It is more than 1,000,000 square miles in extent, a third as large as the United States of America. It especially resembles the great plains and deserts of the American southwest and, like them, is sparsely settled, having only some 6,000,000 people. “Ours is the land that has everything”, Strong cites Kazakhs, “wheat, cotton, livestock, every kind of mineral. We reach from the Ural Mountains to China, from the Blue Caspian Sea to the snows of the Siberian Altai. Half of our land is considered desert, but our Academy of Sciences is exploring it. We have already discovered in this so-called useless desert 240 million acres of land capable of being tilled. Our Ural-Emba oil deposits are the largest in the Union, probably the largest in the world. In copper we are the first in the Union. We have tremendous deposits of other minerals. The only thing we are short of is people. We need many times our present to develop the vast riches of our land”2.

In this context, Strong further explains that since the Kazakhs have more land than they can develop, they invite settlers to come. They pride themselves on their hospitality to new settlers, hospitality has been honored among Kazakhs for centuries. Today, Strong shares, they lay out farms and build homes and then invite the settlers. For example, the author notes, the farmers from other Union republics send delegates to inspect the various possibilities and to choose their future home. They come in large groups and form a whole new village.

Interestingly, like many western travelers who visited Kazakh steppes pre – Soviet era, Strong also notes that the Kazakhs have many legends about horses. For example, she tells about the famous horse Konur-At who died of thirst in the desert. Modern Kazakhs, the author shares, speak of the “great iron horse”, who conquered the desert for all the Kazakh people. Strong explains further noting that they mean the Turkestan-Siberian Railway, the great north-south line across Asia, the first “giant” of the Five Year Plan. Today in the desert, Strong highlights, stands a flourishing copper town reached by rail. It is Kounrad, named for the horse3.

At Aina-Bulak, the author notes, a once-empty spot in the plains, representatives of many Soviet nations, amid cheers from the mighty gathering, added their blows to drive the final spike at the opening of the “Turk-Sib Railway”. According to the author, this spike united Siberia with Central Asia. It changed forever the life of half of a continent, it joined two streams of life – the one along the forest rivers of Siberia and the caravan life of the southern plains. The center of this new united life, Strong adds, is Kazakhstan.

“The center of this new united life is Kazakhstan.”

The author also notes that all over Kazakhstan was heard the tapping of geologist’s hammer. New cities arose to develop newly found mineral deposits. Emba became a great oil center; Aktiubinsk became a chemical city, turning beds of phosphorite into fertilizer. In the empty desert arose Karaganda, a city of 160, 000, the center of the third largest coal region of the USSR. The meat packing plant in Semipalatinsk grew to the size of the big packing plants in Chicago.

“The meat packing plant in Semipalatinsk grew to the size of the big packing plants in Chicago.”

According to Strong, one discovery made in Kazakhstan was to prove of strategic importance during the World War II. For instance, rubber-bearing bushes were found growing wild on the dry plains; they are “kok-sagyz” and “tau-sagyz”. Most of the world’s natural rubber comes from the tropics, Strong explains, and Japan’s seizure of the South Sea areas handicapped the United Nations. But the Soviet Union, the author notes, was already making most of its own rubber, partly synthetically from chemicals and partly from plantations of plants that once grew wild in Kazakhstan4.

Strong also describes the rapid growth of cities in Kazakhstan. For example, she says that in ten years Alma Ata grew from a hill town of 60,000 to a garden city of 260,000 with long avenues shaded by poplars and tiny irrigation streams flowing in the gutters, giving coolness to the air. It boasted its new apartment houses, its parks; its recreation lake for swimming and boating, made by damming the mountain streams. It boasted still more its 7000 university students in fourteen different facilities, preparing to give the technical leadership to Kazakhstan’s growing life.

“The greatest wealth of a land is people”, they repeated in Alma Ata. “We have good people in Kazakhstan”.

Here was Satpeinov, the first Kazakh geologist, Strong says. Born in a nomad herdsman’s family, he discovered the biggest copper deposits in the Soviet Union. Here was Berseyev, Strong adds, a Kazakh farmer who claims the world’s record in the growing of millet – of which he secured five metric tons to the acre.

Alma Ata newspapers, Strong observes, are full of the exploits of Kazakh farmers, workers, scientists and artists. One night a new opera opens in the Kazakh National Opera House. It is by a Kazakh composer about the history of the Kazakh people. One summer, 1940, the young folks built five hundred miles of railroad to connect Karaganda coal with the iron of Magnet Mountain; the next year they built a longer railroad to the Emba oil.

This life, Strong explains, leaped once from the nomad epoch to the airplane. To tame the great plains of Kazakhstan, according to the author, the railroad proved too slow. From Alma Ata airport the planes set forth in all directions, exploring the republic’s wealth. After they find the riches, they build roads and railroads to get them, the author concludes.

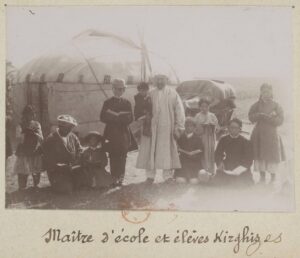

Interestingly, according to Strong, the most famous man among the Kazakhs is not a warrior nor a government official but the aged minstrel Djambul. He is nearly a hundred years old and has been singing on the plains of Kazakhstan for eighty years. Djambul was born in 1846, the son of a herdsman. He was gifted with the talent for improvising songs. From the age of fourteen he sang in the herdsmen’s camps for a crust of bread or a night’s lodging. As a young man, courting, he sang for a whole day before the yurt of his beloved, never repeating himself once. Djambul’s songs are translated into many languages of the USSR, he is known throughout the Union, – the author adds. On May 20, 1938, a jubilee was celebrated throughout the USSR – the seventy fifth anniversary of Djambul’s singing.

When Hitler struck at the USSR, Strong says, all the Kazakh people felt it as a personal blow. Two-thirds of the elected members of village governments and forty members of the Supreme Soviet of Kazakhstan – their national congress – went to fight on the distant battle front. Thousands of Kazakhs won decorations in battle, the author says. Kazakhs took part in the famous fight of the twenty-eight men of the Panfilov division, who stopped fifty German tanks at the gates of Moscow and destroyed them all before they themselves were destroyed. Tens of thousands of other Kazakh heroes defended Moscow, Leningrad and Stalingrad, the author highlights.

Moreover, Strong emphasizes that during WWII, Kazakhstan had another task in addition to fighting. It furnished food for the war. Kazakhstan increased both its grain and its meat deliveries, even though its able-bodied men had gone to war.

To conclude, we hope that our readers will enjoy this interesting volume about Kazakhstan’s rapid industrial development in pre-WWII era. This year, the world celebrated the 75th anniversary of the great victory and Kazakhstan’s contribution to global peace and security will be remembered forever.